by Lil Tuttle

Holiday feasting is an annual tradition, which is why so many of our New Year’s resolutions are, sadly, about dieting. If weight loss is on your to-do list, take a little time to plan for success.

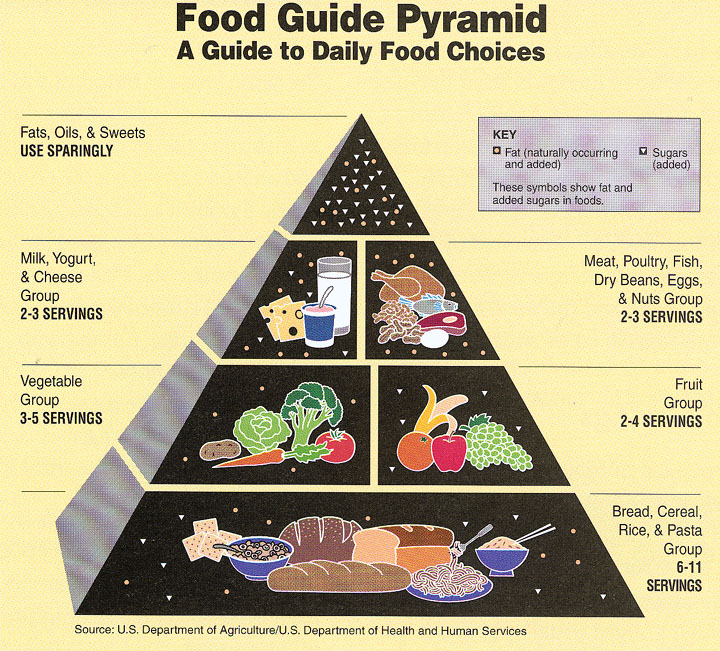

You’re probably better off, for instance, ignoring the familiar federal government’s Food Guide Pyramid: a Guide to Daily Food Choices. This particular chart (right), promoted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture from 1992 to 2005, had the nation counting calories while filling its collective dinner plates daily with disproportionately high servings of carbohydrates.

You’re probably better off, for instance, ignoring the familiar federal government’s Food Guide Pyramid: a Guide to Daily Food Choices. This particular chart (right), promoted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture from 1992 to 2005, had the nation counting calories while filling its collective dinner plates daily with disproportionately high servings of carbohydrates.

We’ve learned a lot from science since then about how those carbs are metabolized by the body. The New York Times recently reported on the latest study by Harvard researchers.

It has been a fundamental tenet of nutrition: When it comes to weight loss, all calories are created equal. Regardless of what you eat, the key is to track your calories and burn more than you consume.

But a large new study published on Wednesday in the journal BMJ challenges the conventional wisdom. It found that overweight adults who cut carbohydrates from their diets and replaced them with fat sharply increased their metabolisms. After five months on the diet, their bodies burned roughly 250 calories more per day than people who ate a high-carb, low-fat diet, suggesting that restricting carb intake could help people maintain their weight loss more easily.

The new research is unlikely to end the decades-long debate over the best diet for weight loss. But it provides strong new evidence that all calories are not metabolically alike to the body. And it suggests that the popular advice on weight loss promoted by health authorities — count calories, reduce portion sizes and lower your fat intake — might be outdated.

Harvard researcher David Lugwig (co-director of the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School) explains more fully in an op-ed in the LA Times entitled The Case Against Carbohydrates Gets Stronger:

[F]indings from a new study I led with my colleague Cara Ebbeling suggest that what we eat — not just how much — has a substantial effect on our metabolism and thus how much weight we gain or lose.

People have a hard time believing that weight control isn’t just a matter of calories eaten and calories burned. But there is an alternate hypothesis about obesity, which is what my group studies. The carbohydrate-insulin model argues that overeating isn’t the underlying cause of long-term weight gain. Instead, it’s the biological process of gaining weight that causes us to overeat.

Here’s how this hypothesis goes: Consuming processed carbohydrates (especially refined grains, potato products and sugars), causes our bodies to produce more insulin. Too much insulin, one of the most powerful hormones, forces our fat cells into calorie-storage overdrive. These rapidly growing fat cells then hoard too many calories, leaving too few for the rest of the body. So we get hungry, and if we persist in eating less, our metabolism slows down.

Once our metabolism slows down, apparently it’s game over: the weight wins.

What happens, though, if we reduce the amount of carbs we eat?

Ludwig’s study randomly assigned participants to eat exclusively one of three diets, containing either 20%, 40% or 60% carbohydrates.

Participants in the low (20%) carbohydrate group burned on average about 250 calories a day more than those in the high (60%) carbohydrate group, just as predicted by the carbohydrate-insulin model. Without intervention (that is, if we hadn’t adjusted the amount of food to prevent weight change), that difference would produce substantial weight loss — about 20 pounds after a few years. If a low-carbohydrate diet also curbs hunger and food intake (as other studies suggest it can), the effect could be even greater [emphasis added].

This result could explain in part why U.S. obesity rates have been going up for decades. Individuals have a sort genetically predetermined weight — lighter for some, heavier for others. Despite this, the average weight for American men has gone from about 165 pounds in the 1960s to 195 pounds today. Women, likewise, have gone from an average of 140 pounds to about 165.

Dr. Frank Atkins, a diabetics expert, discovered and wrote extensively about the power of low-carb diets beginning in the 1970s. But government didn’t pay any heed. Apparently it still isn’t.

If a resolution to lose (or even to sustain a good) weight is in your future, check out the Atkins website. You’ll find recipes, meal ideas, charts, and more information about how and why a low-carb diet works the way it does. It could put you on a path to personal success in the new year.