The Census Bureau had only one job: count the population for the purpose of apportioning political representation and direct taxation. Yet since 1960, when the Census Bureau stopped collecting citizenship information on every U.S. resident, census-taking has evolved into a powerful tool of ethnic lobbyists seeking preferential federal government treatment and the benefits associated with it.

Race and ethnicity questions on census questionnaires are not new, although they were generally inserted when such information was believed necessary to fulfill the Census Bureau's constitutional mandate related to representation and taxation.

A "Race" question was part of the original 1790 census, for example, when in the early days of American history blacks were counted as 3/5 of a person for representation purposes.

Following the first mass wave of immigration in the 1840s, a "Place of Birth" question was inserted in the 1850 census to distinguish between native-born and foreign-born persons, and citizenship/naturalization questions were asked of everyone between 1890 and 1950.

"Indian" was inserted in 1860 to distinguish between "Taxed American Indians" who chose U.S. citizenship rights with taxable status and those who retained non-citizenship tribal rights with non-taxable status.

Ethnic Group Lobbying

Ethnic questions on census forms at the bidding of special interest groups seeking preferential federal treatment and benefits, however, are a relatively new phenomenon, as the evolution of the Census Bureau's "Hispanic Origin" question illustrates.

Mexican-American advocates were offended when, in 1930, the Census Bureau first introduced "Mexican" as a Race/Color category. Mexicans had always been counted in the white race since they were deemed to be of European Spanish descent, and advocates fought to retain their white racial status. With assistance from the Mexican government, activists lobbied successfully to have the "Mexican" designation removed from the 1940 census.

Hispanic lobbyists changed their minds in the 1960s following two major federal legislative initiatives. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments created a preference system giving higher priority to family unification, which was perceived as a huge benefit to Hispanics. Civil Rights legislation—designed to respond to historical mistreatment of black Americans—introduced a unique financial incentive: it became beneficial, in terms of federal social, economic and housing programs, to be identified as a "minority."

Hispanics were still part of the white race, however, so they did not qualify as a racial minority. Seeking another route to preferential federal minority status, advocates lobbied intensively for a special Hispanic identification question in censuses.

Yielding to pressure, the Johnson Administration directed the Secretary of the Commerce to add a new "Hispanic Origin" question to the 1970 Census long form, which was given to a sampling of the U.S. population.

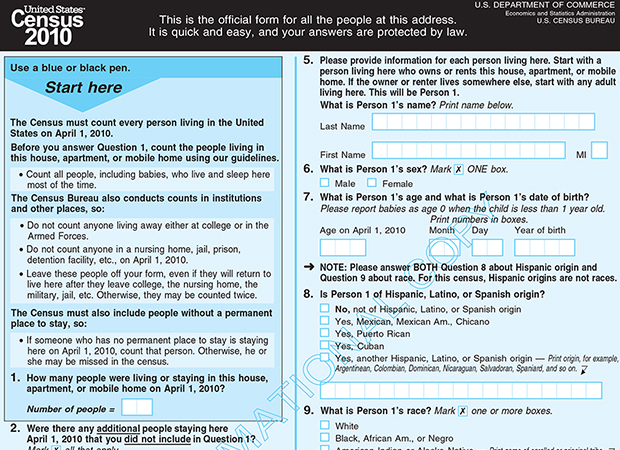

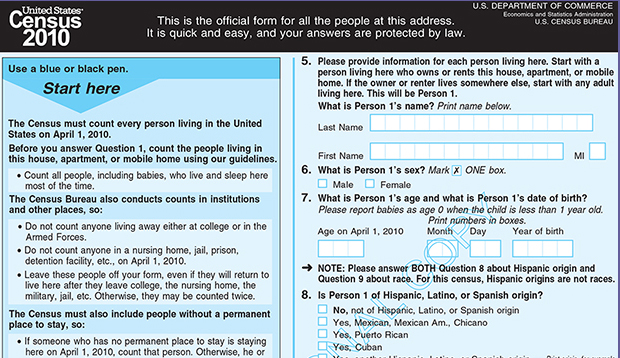

By 2010, the Hispanic lobby achieved unparalleled success when Hispanics became the only ethnicity included in the 10 mandatory questions required of every U.S. resident. Five of the mandatory questions were related to residence and contact information. The remaining five questions were:

- Name

- Sex

- Age/Date of Birth

- Race

- “Is [this person] of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?”

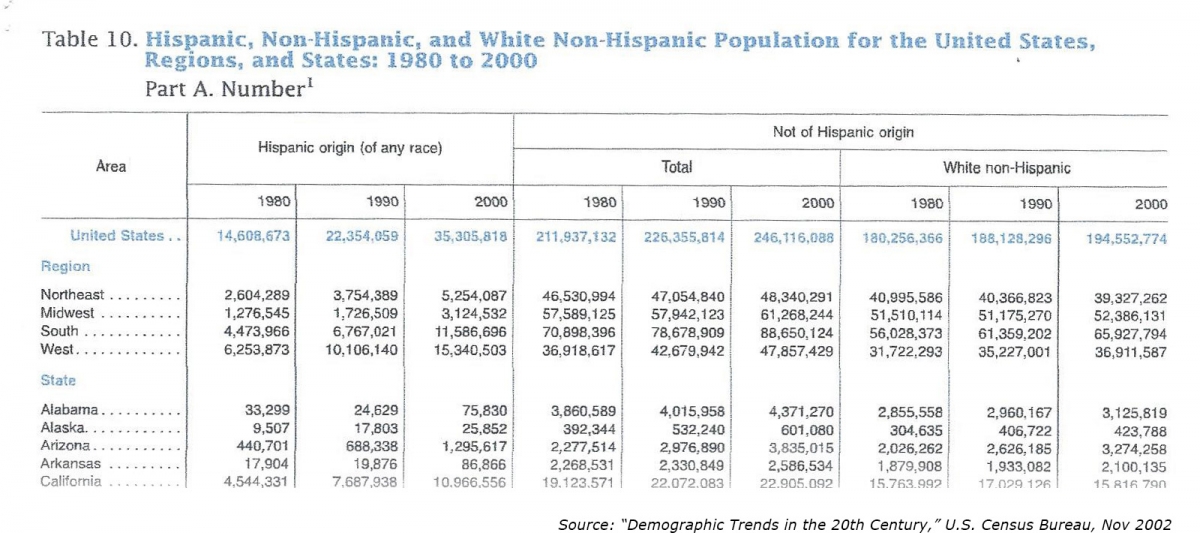

Since the 1980s, the Census Bureau has produced an abundance of Hispanic ethnic reports and data tables. One table (shown below) sorts the U.S. population into only two categories, Hispanic Origin (of any race) and Not of Hispanic Origin, essentially elevating one ethnic group above all other ethnicities and races.

Watching Hispanic lobbyists' success, other ethnic groups—referred to as 'stakeholders' by census officials—began lobbying for their own unique ethnic data collection, according to a 2009 Census Bureau report by Karen Humes and Howard Hogan.

Middle Eastern lobbyists, for example, who had abandoned their petition following the September 11, 2001, attack on New York and Washington, are now poised to get their special ethnic question in the 2020 census, even as the Census Bureau is considering eliminating the “Race” question altogether.

Citizenship Status Matters

If the U.S. population were to be sorted into only two categories, one might expect those categories to be Citizen and Non-Citizen. Yet this information is conspicuously missing. The Census Bureau hasn't required all U.S. residents to identify their Place of Birth and citizenship status since 1950.

This lack of accurate national and state citizenship data deprives policymakers of information essential to the current immigration reform debate. Since 1960, the Census Bureau has gathered citizenship data from only a sampling of U.S. residents. As a consequence, the Census Bureau can only estimate the number of persons who are native citizens, naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents, legal temporary residents, and illegal residents.

State legislative districts today are commonly apportioned based on total population of citizens and non-citizens alike. That may change depending on the outcome of Evenwel v. Abbott, a state redistricting case on the U.S. Supreme Court's docket this year. The court is being asked to clarify "whether the 'one-person, one-vote' principle under the Equal Protection Clause allows States to use total population, and does not require States to use voter population, when apportioning state legislative districts." Since voting is a citizenship privilege, an accurate count of native and naturalized citizens would become essential if the Court decides in favor of voters.

Regardless of the outcome of this case, American citizens—of all races and ethnicities—are the primary stakeholders in census data collection, and their interests are diminished by self-serving ethnic lobbyists.

Congress has the power—and should use it—to curb ethnic lobbyists' abuse of the census process and to require collection of citizenship status of all U.S. residents on all censuses.

Sources:

“Census Considers New Approach to Asking About Race – by not using the term at all,” D’Vera Cohn, Pew Research Center, June 18, 2015

“Measurement of Race and Ethnicity in a Changing, Multicultural America,” Karen Humes and Howard Hogan, Spring Science+Business Media, LLC, 17 September 2009

"Supreme Court to Consider How to Calculate Size of Voting Districts," Jess Bravin, Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2015