by Lil Tuttle

Americans historically viewed their nation as the great melting pot of individuals, eschewing efforts to pigeonhole citizens into distinct groups or categories. Yet a new large-scale national survey released this month, Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape, does just that, categorizing Americans into seven “tribes.” Finding “deep polarization and growing tribalism” in the U.S today, the authors call for compromise, but they leave unanswered the question as to how to achieve compromise when presented with diametrically opposed visions for our nation.

Seven American “Tribes”

The study examined “five dimensions” of individuals’ core beliefs: (1) tribalism/group identification; (2) fear/perception of threat; (3) parenting style/authoritarian disposition; (4) moral foundations; and (5) personal agency/responsibility.

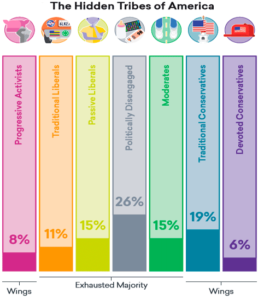

The study finds that this hidden architecture of beliefs, worldview and group attachments can predict an individual’s views on social and political issues with greater accuracy than demographic factors like, race, gender, or income. The research undertaken for this report identifies seven segments of Americans (or “tribes”) who are distinguished by differences in their underlying beliefs and attitudes.

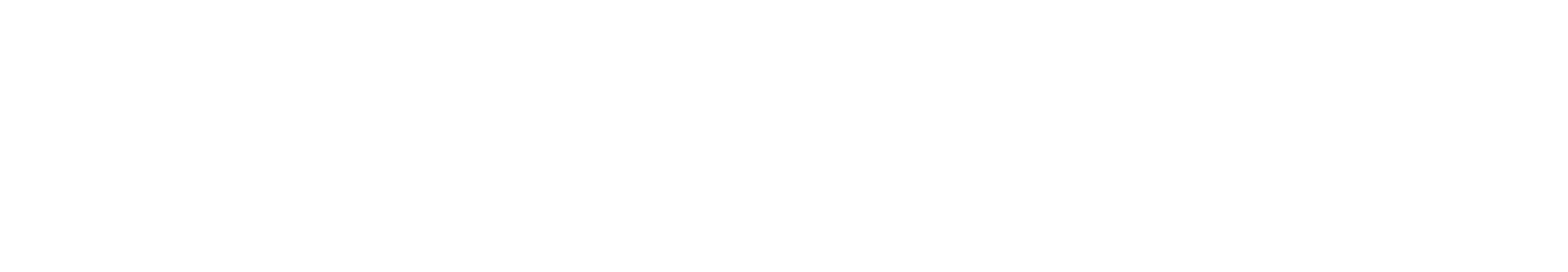

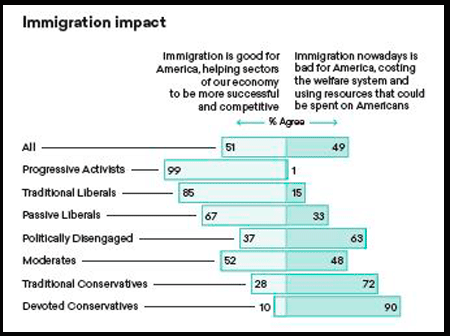

The seven tribes are defined and described as outlined in the graphic below. The categories were based on individuals’ answers to a subset of 58 core questions, none of which “related to current political issues or demographic indications such as race, gender, age or income.”

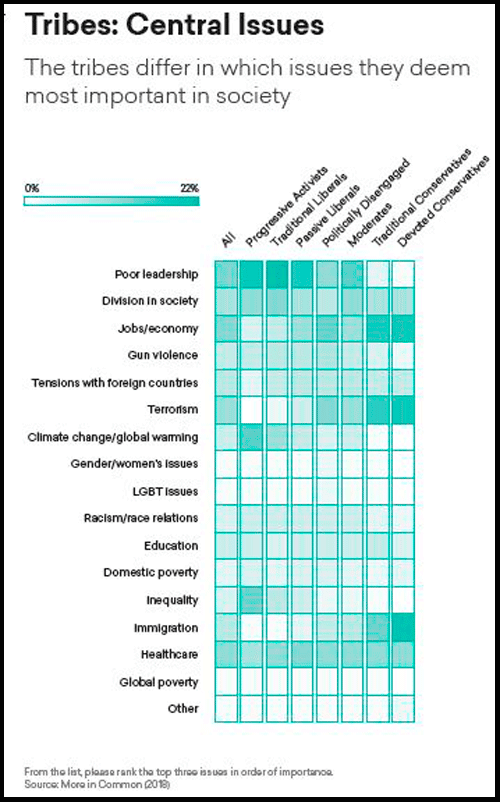

Researchers found that views on current political topics were generally consistent within each tribe, as the graphic below demonstrates.

Issues that Matter to Each Tribe

The chart of each tribe’s Central Issues suggests there are areas of potential agreement among the various tribes.

Wings & the Exhausted Majority

Researchers labeled the most-left and most-right tribes as “Wings.”

Progressive Acxtivists, the most liberal group, and Devoted Conservatives, the most conservative, show strong degrees of consistency within their ranks, while being almost perfectly at odds with each other. Middle tribes, by contrast, orient themselves incrementally on the ideological spectrum.

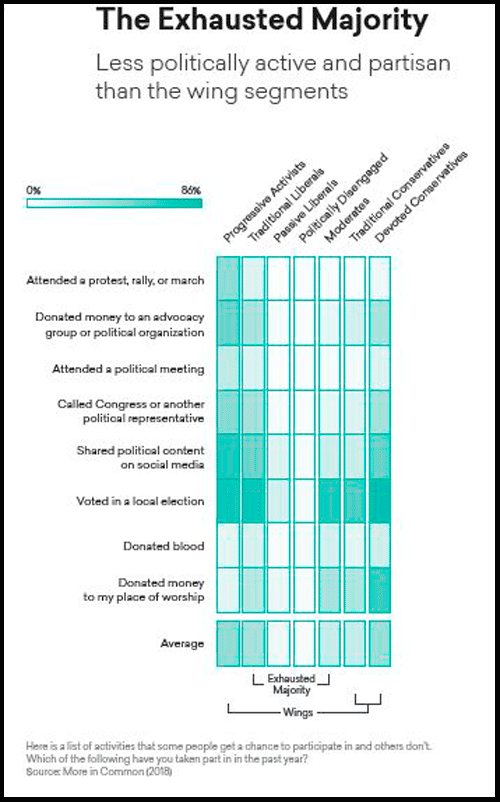

Members of the middle tribes, labeled the “Exhausted Majority,” are “less politically active and partisan than the wing segments.” They hold diverse views, yet they are “frustrated with the status quo and the conduct of American politics and public debate.”

One troubling aspect of this particular graphic is the labeling of Traditional Conservatives as part of the “Wings” group, while Traditional Liberals are labeled as part of the “Exhausted Majority.”

Yet if the chart shading is an accurate representation, Traditional Liberals are more politically active than Traditional Conservatives. In greater numbers and/or intensity than their Traditional Conservatives counterparts, Traditional Liberals (a) donated money to an advocacy group or political organization, (b) attended a political meeting, (c) called Congress or another political representative, and (d) shared political content on social media.

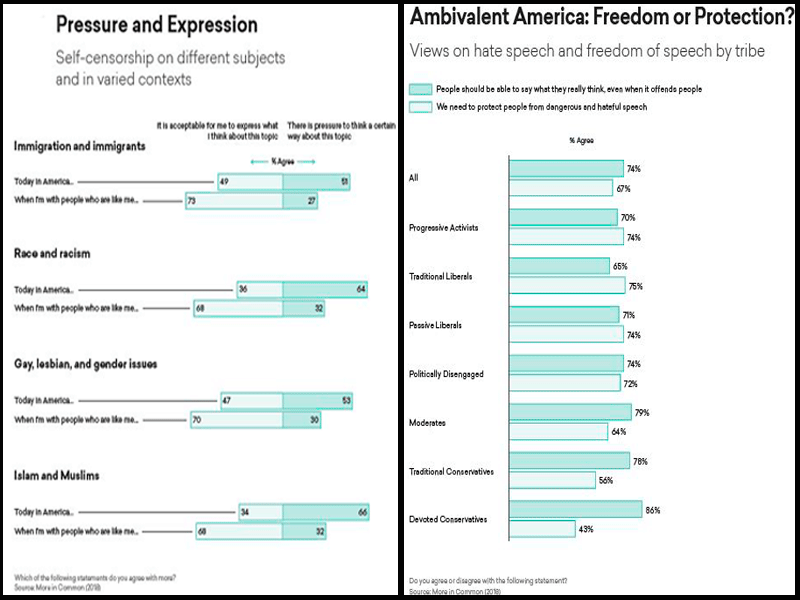

Political Correctness & Speech

One of the most widely reported results of the study was the finding that 80 percent of all respondents agreed that “political correctness is a problem in our country.”

The study also found that “82 percent of Americans agree that hate speech is a problem in America today.” Yet the Ambivalent America graphic (below) suggests a far more puzzling story. Americans seem to hold simultaneously competing views: 74% believe in the freedom to say what one thinks, while 67% believe in protecting people from hate speech. That’s more than ambivalence; it’s an incompatibility.

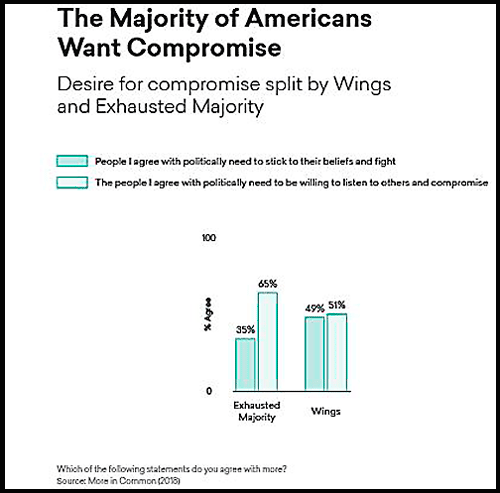

Compromise

The study reported that a majority of Americans want compromise (graphic below). Yet it is hard to envision what compromise would look like in some of the issues on the political menu today — free speech vs. controlled speech; socialist economy vs. free market economy; open borders vs. rule of law; etc. These are not inconsequential matters for the future of the nation.

Joy Pullman addresses compromise in an excellent piece on political correctness at thefederalist.com.

“Hidden Tribes” was published by an international group of largely left academics and political organizers called More In Common. One of their goals is to “Develop and deploy positive narratives that tell a new story of ‘us’, celebrating what we all have in common rather than what divides us,” with the goal of reducing political divisions, such as those leading to Brexit and Donald Trump’s election. This likely reflects sociological research outlined by folks like Jonathan Haidt that emphasizing differences, such as promoting multiculuralism instead of patriotism, is bad for national cohesion.

This has obvious temporary benefits but also shunts aside questions about whether compromise is the just thing to do about political questions that have strong moral bases. Sometimes compromise is just another word for “I don’t want to think about this deeply.” [snip]

[C]ompromise may be the only pragmatic option, but it’s not necessarily an ultimate good. In fact, division can be useful by providing clarity about the serious moral disagreements underlying many political debates. What’s not good is division for the sake of division, which is often currently labeled tribalism.

Compromise can also be another word for giving in and giving up to political opponents. The right side of the political spectrum has done more than its share in that regard. So much so that the Left now expects its opponents to immediately surrender at the first accusation or protest.

Perhaps the reason our political landscape is in its current polarized and tribal shape is that the Right is finally taking a stand on important issues that affect our nation’s common good.