by Katharine Cornell Gorka

Two of the predominant ways of looking at the problem of ISIS are either as a sociological problem or as a theological problem. The Obama administration takes the first view; its critics take the second.

From the beginning of his presidency, President Obama has deflected blame for terrorism away from the religion of Islam. For him and his administration, the fault lies not with the religion but in 'upstream factors': economic, political, and sociological causes.

President Barack Obama speaks at Cairo University in Egypt, 2009

In his seminal Cairo speech, delivered at Al-Azhar University in Egypt on June 4, 2009, President Obama identified three explanations for Muslim discontent and violence:

- colonialism, by which the West denied rights and opportunities to Muslims;

- the Cold War, which led the West to treat Muslims as proxies and to disregard their aspirations; and

- modernization and globalization, which bred Western hostility toward Islam.

According to this view, Muslim extremism is driven by legitimate grievances and has nothing to do with factors that might lie within the religion itself. The policies that naturally follow from such a view gloss over the role of religion and focus instead on addressing those alleged grievances.

Thus has the administration proceeded. In numerous speeches President Obama has expressed his support for Islam and its importance to the United States. He provided verbal, financial and technical support for anti-government forces during the Arab Spring (which included support for both secular forces as well as Islamist parties). And he withdrew nearly all combat troops from Iraq in 2011 and from Afghanistan in 2014.

If U.S. "meddling" in the region as well as perceived Western hostility toward Islam were in fact the root causes of Islamist terrorism, then these new policies could reasonably have been expected to bring about the demise of Al Qaeda, ISIS, al Nusra Front, Boko Haram and other Islamist groups.

But they did not. Indeed, we have seen the very opposite.

When President Obama came into office, Osama bin Laden was in hiding and Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) had all but disappeared. Since that time,

- AQI evolved into ISIS, declared the Caliphate, and took over a territory the size of Great Britain with fully functioning affiliates in 18 countries;

- Syria erupted into a civil war that has now raged for more than 5 years, claiming the lives of more than 400,000 and setting off the largest refugee crisis the world has seen;

- Osama bin Laden is dead, but Al Qaeda is resurgent under the leadership of Ayman al Zawahiri;

- Libya is roiled by civil war and chaos;

- Boko Haram continues its war against Christians and moderate Muslims in Nigeria;

- the Taliban rules in much of Afghanistan; and

- the jihadists have brought their violence to the West with deadly attacks throughout Europe and the United States.

There could be no clearer evidence that the current strategy against Islamist violence is failing.

Reassessing the Threat

Where does the solution lie? First, it requires a revised assessment of the threat. The sociological assessment of the threat is wrong. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that grievances are not the key cause of extremism. Jihadists, as a rule, are not undereducated or underprivileged.

While upstream factors might be exacerbating, ideology is a far more important motivator. The problem is that the ideology of jihad is inextricably rooted in religion and this notion makes most Americans profoundly uncomfortable.

From 4th grade civics classes onwards, Americans are schooled in the notion that others should not be judged for their religion. It is far easier and more comfortable to blame poverty or tyrants or even ourselves for Islamist terrorism. But we must get over this squeamishness when it comes to talking about religion, because religion is central to the conflicts in the Middle East.

Abu Bakr al Baghdadi (Aljazeera)

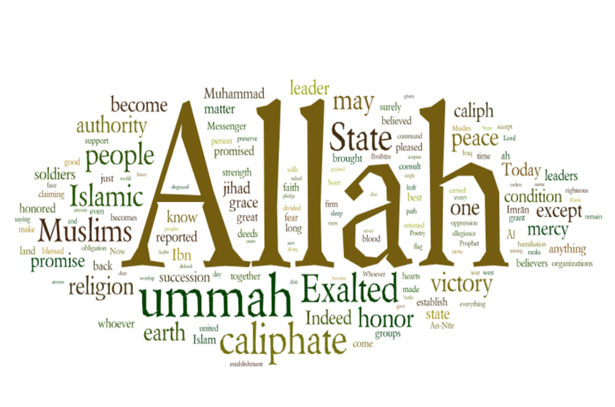

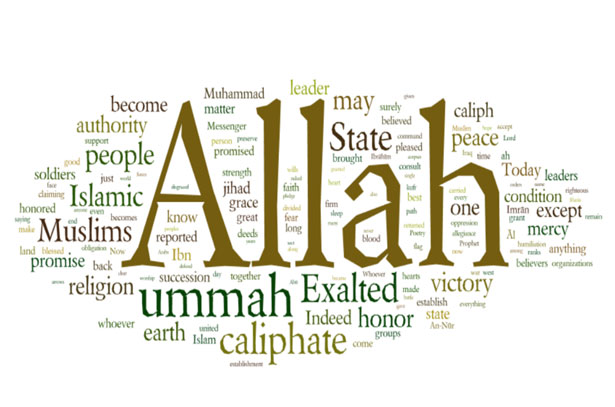

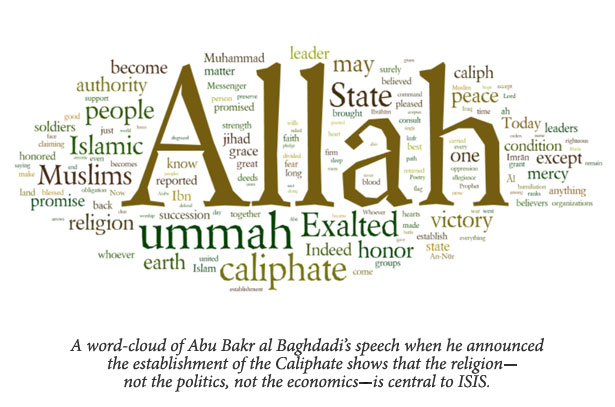

When Abu Bakr al Baghdadi declared the establishment of the Caliphate on June 29, 2014, his concern was not poverty or modern nation states or democracy; it was Islam. A word-cloud analysis of his speech makes that incontestably clear:

All the evidence that has since emerged from the Islamic States only serves to reinforce that fact. Most recently, a defector from ISIS, Mohammed Imal Khweis, said, "Our daily life was prayer, eating and learning about the religion for 8 hours."

Fault Lines Within Islam

The civil war that is happening within Islam across the globe has much more to do with fault-lines within the religion than it does with economic or sociological factors.

Those fault lines originated with the death of Mohammed, and they come down to two key questions: Who is the successor to Mohammed, and what are the sources of authority in Islam?

After Mohammed completed his last pilgrimage and shortly before he died, in 632 A.D., he is said to have preached for three hours in the blistering sun to more than 100,000 of his followers at Ghadir Khumm. There, he took the hand of Ali, his cousin and son-in-law, and said, "For whomever I am his Leader, Ali is his leader."

Was Mohammad appointing Ali his successor, as the Shi'a believe? Or was he merely saying that Ali was deserving of esteem and affection, as the Sunni believe?

This lack of clarity over Mohammed's successor led to the assassination of three of the first four caliphs and the eventual division of the Muslim community into Shi'a and Sunni.

Today, this debate over the rightful successor to Mohammed continues to fuel enmity between Sunni and Shi'a: it drives Turkey's and Saudi Arabia's support for Sunni Islamists in Syria against Iran's support for the Shia in Syria and Iraq.

The second fault line within Islam today arises over the question of who has authority in Islam, particularly with regard to the law. During Muhammed's lifetime, the putative revelations he received helped him to elaborate the faith. Some of the pre-Islamic tribal laws and practices remained in place, but in many instances Muhammad laid down new laws and new ways of conducting oneself.

Indeed a part of what makes this body of rules—Sharia, as it has come to be known—so distinctive from the Western concept of law is that it is not merely a set of laws but rather an all-encompassing way of life. Sharia includes laws on ownership, inheritance, divorce, and slavery, but it also includes guidelines on how to pray, how to wash, how to relate to others, even how to enter a room.

This was distinct from the Christian tradition. Jesus Christ had introduced a new set of rules for the spiritual life, to be practiced by his followers while living under Roman laws (the "Render unto Caesar" passage). Mohammad presented a comprehensive system which provided both spiritual guidelines as well as laws. Christians saw themselves as a subset that had to live within a broader society. Islam saw itself as the whole society.

Thus those Muslims who argue for theocracy have all the theological ammunition they need to justify it.

As long as Mohammad was alive, he was the arbiter of the law because he was both the leader of the community and the conduit to Allah. He delivered the word of Allah on what was right and wrong, allowed and forbidden. The Muslim community thus lost its direct access to divine revelation when Mohammed died.

Only a handful of crimes had been explicitly named in the Qu'ran: theft, fornication, false accusation, and the waging of war against Islam or "spreading disorder in the land."

What happens when situations are encountered that had not been specifically addressed by Mohammad?

Post-Mohammad Division

Since the Qu'ran was the word of Allah, as conveyed by Mohammad, was the Qu'ran the only legitimate source of law? Or since Muhammad was the chosen messenger of Allah, were his words and deeds outside of the Qu'ran also an authoritative source?

And what about the Rightly Guided Caliphs, those companions of Muhammad who had lived and worked alongside the Prophet and after his death had been so favored by Allah with victory in expanding the empire of Islam? Were not their elaborations of the law in those first decades after the death of Muhammad also an authoritative source? Similarly, were not the scholars and inhabitants of Medina a source of authority by virtue of having preserved the practices of Mohammad?

And finally, what about the role of human reason? Could man use reason to draw analogies between circumstances encountered by Muhammad and the present day?

These are the contours of the debate that ensued in the centuries following the death of Mohammad.

Four principal schools of law emerged, all of which agreed on the most important sacred sources, albeit with differences of emphasis among them:

- the Qu'ran,

- the words and actions of Muhammad (as preserved in the hadith and the sunna),

- the example of the Companions of the Prophet, and

- tradition.

The Role of Reason

But passionate and murderous debate ensued over the role of reason.

A group of scholars who came to be known as the Mu'tazalites emerged around the 8th century. They argued that there is an objective moral order that man can know through reason, and therefore human reason must be considered a legitimate source of authority in Islam. (This is an argument very similar to theories of Natural Law that had been developed from Greek philosophy and later Christian theologians, and to which the Mu'tazilites were exposed through translations.)

For a brief time, the Mu'tazalites held sway, and those who argued that reason had no role to play were threatened, flogged, imprisoned, banished, even murdered—indeed this period is referred to as Islam's Inquisition (Mihna). But then the tables turned and those who stood in favor of reason were themselves quashed.

One of the most contentious debates sparked by the Mu'tazalite movement concerned the nature of the Qu'ran.

Not dissimilar to debates in the early Church over the nature of Jesus Christ—is Christ human or is He divine?—for Muslims the question was whether the Qu'ran was uncreated, co-eternal with Allah, or created. According to the Mu'tazalites, logic dictated that the Qu'ran could not be co-eternal with Allah because Allah must have preceded his own speech.

Why does this seemingly obscure point matter so much today? Because if the Qu'ran was uncreated, co-eternal with Allah, then it must remain true for all time and its laws and proscriptions must be followed to the letter.

This is the foundation of the argument of groups such as Al Qaeda and ISIS in establishing 7th century rules and punishments. If, on the other hand, the Qu'ran was created for a specific time and place, then it can be adapted and amended for a new time and place.

Here lies the greatest potential for Islam to adapt to the modern world, to live peacefully alongside other religions, to end Islamist violence. Unfortunately, the Mu'tazalites were thoroughly defeated by about the 10th century, and those who have tried to revive the Mu'tazalite argument have been equally plagued.

These are the very profound fault lines within Islam, of which ISIS and Al Qaeda are but one manifestation. Asserting that terrorism has nothing to do with religion, as President Obama has done, is to ignore the very real conflict within the Muslim world.

To think that the United States can have a constructive role in this process by merely taking out key leaders of terrorist groups with drone strikes is to miss the point entirely. This is not a conflict of our making, nor is it ours to solve, but without a doubt the United States has an important role to play. Understanding the religious dimension of the conflict is the starting point in ensuring that it is not an exacerbating one.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Katharine Cornell Gorka is the President of the Council on Global Security and co-editor of Fighting the Ideological War: Winning Strategies from Communism to Islamism. In her current position, Katharine focuses on the threat posed by Islamic terrorism and radical ideologies. She works closely with U.S. government agencies, law enforcement and the intelligence community. Katharine is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and received a master’s degree in International Political Economy from the London School of Economics.